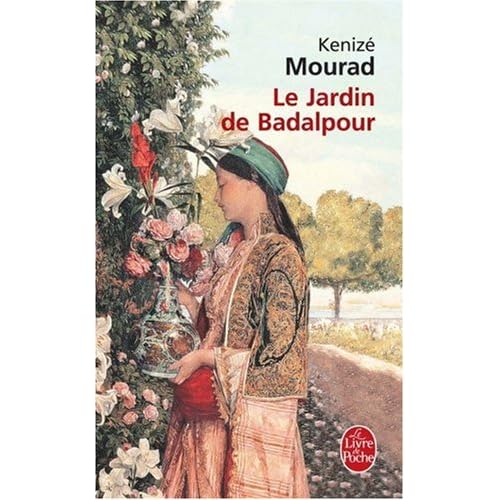

Cover art: John Frederick Lewis (1805-1876)1, Lilium Auratium;

the vase is an Iznik (?) Imari2

the vase is an Iznik (?) Imari2

Kenize Mourad, granddaughter of the last Sultan of Turkey, and daughter of the former Raja of Badalpur, comments early in her book3, while describing her father's obsequies in the old family seat somewhere "near" Lucknow:

De compassion, aucun de ces paysants n'aurait l'idee d'en eprouver pour cette homme qui fut leur maitre mais sut aussi les proteger, les aider dans l'infortune et accompagner leur vie non sans bonte, les exploitant moins qu'il n'est coutume. Car ceux qui exercent le pouvoir ne sont plus consideres comme des humains, de par leur puissance ils appartiennent a l'univers des dieux. Et qui aurait pitie des dieux?

Suddenly I am seized by fear and foreboding: what does Kenize Mourad, raised and educated in France-egalite, know about divine kingship of the feudal society? In her first chapter she discusses frankly her emotions: anger at the family for not having notified her earlier of her father's critical condition, grudges at her brothers for having been brothers (and thus more important in her father's eyes), at her father for -- as yet we do not know what.

But do we -- do I -- want to know?

Mme Mourad sounds like a modern French woman: confident, proud, and prepared to bare her emotional entrails which she is convinced are important and deserving of universal knowing. (Georges Sand comes to mind). Modern French women are no doubt interesting in their own right; but there seems to be just one way of being a modern French woman, and we already know what that is... More importantly, can one expect them to tell us anything truly insightful about the lives and minds of real kings and princes of another time and place, even if they should be their own flesh and blood?

I will read on Kenize Mourad, but gingerly and with trepidation. I have already heard everything westerners -- especially women westerners -- have had to say about Indian divine kingship, religion, love and family relationships, and I am sure I do not want to read it yet again.

*

This is just the gist of my misunderstanding with Angelica, too. I had told her that the emotions and the inner states of knights are a closed book to pretty much everyone knights ever meet in the modern world. She did not believe me: "If you behave in a certain way, she says, people will always understand it". But then -- how could she possibly believe me?

Akhila has known me longer and closer; she is also older and more perceptive: "I don't get you", she says with a winning smile. That, of course, is what one aims to achieve: since to be known is to be available: to be scrutable is to be common.

1 Lewis was a so-called Orientalist, and long dead and forgotten before that term was thrown into opprobrium. In fact, the fortunes of his art revived suddenly in the 1970's, just about the time when the infamous essay by Edward Said was being hatched; from nothing his works quite suddenly began to command seven figure prices. (Indeed, was Said perhaps responding to Lewis's reviving fame?) I'd like to read more about how Lewis was revived. Anyone can recommend a book?

2 To this day the most popular style of pottery decoration in Morocco is a kind of homw-grown variation on Imari. Is this the case across the Arab world?

3 Le Jardin de Badalpour, not, apparently, available in English, though, like the Kawabata-Mishima letters, you could read it in half a dozen other European languages any day of the week.

No comments:

Post a Comment