Mar 31, 2009

Dead end

One could propose a sort of Turing test for aesthetics: if a person has nothing interesting to say about, say, Schoenberg, then it is irrelevant whether or not he likes him; for aesthetic purposes his mind do not exist.

Mar 30, 2009

More intelligent life please

I am reminded by much of it of the god-awful Messiah which I was obliged to hear in Chiang Mai, Thailand, once. My neighbor said, oh, isn't it great? Sure they are doing it badly, but they are doing it and in time they will get better, just you wait. But I didn't want to wait and left, feeling that the Messiah should be performed well or not at all. A lousy performance of Messiah is as good as half a parachute. And so is all middle-brown (read: dumbed-down) culture.

Knowing in advance that no good discussion is ever to be had on internet, I didn't write this reply, but in another issue of the same publication someone else did, an American, as it happens, saying that all of this culture consumption is really nothing but shallow collecting of qualifications to be put in one's Facebook profile; nothing more than a burnishing of one's online personality; an empty show. The implication was that this was shallow and fake. The author went on to quote someone else who said that modern youth was growing up culturally well qualified but immoral. The immorality was measured by supposed readiness to plagiarize as long as one got away with it.

Why did I say "American as it happens"? Because of the moral turn of the criticism. Morals are serious business with the Americans, so serious in fact, that nothing else is. Thus, if you are going to say something weighty in the US of A, it must be moral. (Or else it is nothing).

I got sufficiently ticked-off this time to write a reply. (Mea culpa). I wrote:

"I too find most of these cultural qualification displays on Facebook empty; but, not being Anglo-Saxon perhaps, am not inclined to jump immediately to a moral critique. (Why is everything important immediately moral with you people?) The problem with all these cultural qualifications, it seems to me, is not that their owners do not see a problem with plagiarism (I am not sure that plagiarism is a problem; certainly Bach did not think so, whom am I to disagree); or are inclined to rob a bank; or be otherwise despicably immoral in some really despicable ways; but that they have nothing interesting to say about all the books they read and all the music they hear and all the art they consume. Read the blog entries and their comments. They are all shallow and dull; occasionally a brave effort results in what is at best a cute pirouette. All that experience and all these qualifications seem unable to stimulate the little minds to produce an original, interesting thought.

It's very very bad, George, but it is not a moral issue."

It is a lot worse than plagiarism, in fact: intellectual conversation is dead. Other comments on same the article made this point abundantly plain.

One comment jumped out for me. A fellow signing himself Mahratta wrote:

"The author's assertion that appreciation of culture should not simply be a hollow self-advertisement but should be taken as a true personal mission strikes me as particularly important. Regretfully, this is the only section of this opinion piece that I can identify with."

Regrettfully, I do not know where to go to read more of Mahratta.

Mar 29, 2009

And besides

So how comes it, that after cautioning us against taking artifacts of the past as examples of the tastes of the times, Eco proceeds to do just that?

Mar 28, 2009

Regarding Eco's motivation

In the Jacques Rivette movie Va Savoir there is a scene of a tense dinner: former lovers meet for dinner à-quatre with their respective new partners in tow. In the course of the dinner, the new wife begins telling the story of the difficult times she had gone through before meeting her new husband; and how the wisdom of the east – yoga and feng shui – have been her salvation. Her husband interrupts her brusquely to cut himself off from her views:

“As for me, I do not care for the wisdom of the east. The older I get, the more European I feel.”

We had been told he is a doctoral student working on a never-ending thesis on Heidegger; so his interjection may be a matter of an intellectual’s just revulsion at the inanities of the wisdom of the east movement, with its diets, massages, crystals, pyramids, etc. This is understandable: I, too, am irritated by it, though no more than I am irritated by pap versions of the wisdom of the West, or, more generally, stupidity of any sort, anywhere. (Neither yoga nor feng shui represent their respective culture’s most noble intellectual attainment; both are considered somewhat cooky in the countries of their origin also, occupying a position comparable perhaps to speaking in tongues in the west).

But the public nature of the husband’s announcement, and its vehemence, clearly indicates that something else is also at work: embarrassment at his new wife’s stupidity, desire to retain good opinion of himself by ex-wife and her new husband, the wish to state clearly that his current marriage is not a perfect meeting of minds, perhaps to suggest that it could be negotiable.The precise motivation for his outburst is not clear, but the situation provides us at least some possible clues as to what they could be.

But there are no clues at all as to Eco's motivation.

Mar 27, 2009

Why I learned Chinese

I learned Chinese because I learned English. More specifically, because I learned English early, but not too early – aged sixteen; I learned it very well – I command it nearly as well as my native language; and I learned it at the same time as my whole family – my sister especially. The learning coincided with many changes in my life: emigration; great changes in my philosophical outlook; and rapid assumption of adult responsibilities. Within a few short years my whole personality was dramatically transformed.

Since so many variables were changing simultaneously, it would be hard to say to what extent the changes of my personality which took place at the time were a function of switching languages, if any at all. Yet, there is one piece of evidence to suggest that the influence of the change in language was profound: I had grown up very close to my sister; gradually, in the course of the process of settling in our new, English-speaking country, we grew apart. That this had something to do with the language was proven to me by the fact that we got along better in our native language than we did in English; we learned a trick: whenever a problem occurred that seemed to us insurmountable – and this almost always happened when we spoke English – we switched back to our native language and -- the problem evaporated; it suddenly seemed trivial, even funny. At first, we laughed about; since everything we could say in one language we could also say equally well in the other, the dramatic effect of the switch seemed absurd, preposterous. It seemed silly.

(As English became more and more important in our lives, in time we stopped bothering to switch: the English side, mean and confrontational, seemed the more important; it proved unrelenting. We are no longer in contact).

This experience led me to my own version of the Whorf/Sapir hypothesis (about which I was to hear for the first time only some years later). Determined to understand the problem better, I decided to learn another foreign language as well as I learned English; having read that the ability to acquire near-native fluency in a language disappeared shortly after puberty, I realized I had to hurry; suspecting that the effects of language change were the easier to spot, observe, and describe the greater the morphological difference between the languages, I resolved to learn a non-Indo-European language (after some hesitation I resolved on Chinese because I was aware of its ancient literary matching the Western). Thus aged 20 I left for Taiwan.

In this decision I was guided by that intuition which guides all human sciences, linguistics and anthropology especially: in order to escape the confines of perception bias built into our own culture and to obtain a broader selection of data points on human behavior, it is necessary to compare between many different cultures, the more the better, and the less related they are the better.

In the succeeding twenty five years in all my work -- teaching, marketing, finance -- I have made out of this intuition my most important and most fruitful analytical tool: I have routinely compared the practices, theories and data from various cultures in order to learn the difference between the universal and the local aspects of human behavior. In this I was only acting like everyone else in these professions; cross-cultural comparison is the most basic elements of research in all these fields.

The truth of this intuition is so obvious today, that I simply cannot get it through my head that someone, in this case a world famous scholar, would not share it; and would start his two works, widely held to be among his most important, by stating at the outset, that he will not take into consideration other cultures. He seems to me like a linguist who refuses to learn a foreign language.

Mar 26, 2009

That analysis of the history of aesthetic arguments is a waste of time

There is another reason why the educational value of looking at historical aesthetic statements, such as those quoted by Eco, is nil: generally speaking, aesthetic writings, both East and West, have been uniformly awful.

Now, I do not mean their entertainment value: they are often very witty; and sometimes poetic. But their analytical value is just about zero.

To convince yourself, take any aesthetic debate of the past and try to follow it for more than a few paragraphs: read Apollinaire on Picasso; or the great debate between the ancients and the moderns; or the classicists' attacks on the baroque. Hardly any writer attempts an analysis; inveigh is the operative word. Any aesthetic theories proposed, if there are any, are ad hoc and usually patently ridiculous.

I am reminded of a Japanese girl I once heard during a marketing research interview. She explained why she did not soft-drink A: "because a friend said to me (with emphasis and emotion): "yuck! It is salty!" So I switched to B..."

Listen to the child: she tells the truth. This is how aesthetic points are made -- and taken.

Most aesthetic writing is on this pattern: it is either an attack or a defense of something; invariably arguments are used but they are always far weaker than the emotional emphasis of the argument. And it is always the latter that carries the day.

Analyzing the arguments is therefore of very limited interest.

Mar 25, 2009

Eco lies

"We can only speak of our western culture," says Eco, "for in exotic cultures we don't have a theoretical text to tell us whether that mask were intended to cause aesthetic delight, or fear, of hilarity. "

The implication that non-western civilizations have not written aesthetic texts is false. India, Indonesia, China and Japan all have written aesthetic texts; both China and Japan have a rich, thousand year old tradition of aesthetic writings.

Why does Eco lie?

Is he embarrassed to admit that there may be something he does not know? (Or worse: that there may be books he has not read?)

Whatever his reason, he stands firmly in the ancient European tradition of ignorance about other civilizations; worse: ignorance justified by sweeping dismissive misrepresentations to the effect that whatever we, Europeans, do not know is not so much not worth knowing as -- simply -- non-existent.

Perhaps we should reverse this model and pretend that Umberto Eco does not exist.

Mar 24, 2009

Slavoj Zizek

There is something very familiar about Slavoj Zizek: his mind wends in the odd, baffling ways typical of most Russian emigres. He seems to confirm the intuition common across Eastern Europe that Serbs are really Russians.

Kudos to Slavoj Zizek on one account: he believes very firmly that Serbia has something to teach the West. The sheer power of this conviction is very refreshing in the world in which, say, Polish art historians speak breathless pomo-speak lifted verbatim from American academia. And I am sure that it is the case, that Serbia does have important things to teach the West, but as I listen to him I am sadly certain that Slavoj Zizek has not quite discovered what it is.

Mar 23, 2009

Tokyo 1940

It is a puzzling experience.

The novel is about a young Japanese poet coming of age in Tokyo of 1940. Naturally, the interviewer began by asking the author whether he had any special connection or expertise on Tokyo of 1940. In some way it turns out not much: Miller lived in Tokyo "for some time in 1994"; he taught English there, as, he says, "almost everyone else who goes there", suggesting that his was the typical gaijin experience of Japan; by his own admission there is nothing left of old Japan in modern Tokyo; while teaching, he met someone who did remember the fire bombings (still to come at the time in which the novel is set) but "her English was not good enough to learn much from her"; he pronounces 江戸 eat-dough.

On the other hand, he does seem rather well accultured: he is an Ozu Ysujiro fan, a rare taste with most, and a pretty good cultural chronicle of Japan; and he has read his Tanizaki. (He even borrows an idea from Some prefer nettles: a westernizing young man discovering, to his suprise, the ancient and weird world of bunraku; a development which, as the interviewer observes, leads nowhere in the novel; but perhaps Miller is a fellow bunraku fan: all the more kudos to him).

Which leads me of course to my recurrent bafflement about the truthfulness of novels. What does Andrew Miller really know about young Japanese poets of 1940's? And, therefore, why read One Morning Like A Bird? One reason why I have not written a novel about the relationship between Lady Seishonagon and Lady Murasaki, and will not write one about the meeting of Ezra Pound and T.S. Eliot in Paris in 1922, is that I do not believe I can know what they were really like; and that I am more interested in what they were really like than I am in what they could be imagined to have been like.

But what of it? What if Andrew Miller writes a beautiful, sensitive, insightful, wise book about a young man growing up in a time of war? What if it is moving and interesting, provides pleasure and food for thought? Who cares then that the Tokyo of 1940 it portrays is a wholly imaginary city? Why not pretend it is a kind of science fiction novel and that "Tokyo 1940" really stands for the Rings of Saturn or the Empire of the Moon? Miller's discussion of his intention in the novel to describe the moment of unillusion, as he calls, it -- the a sudden sobering up, of scales falling of one's eyes, of confrontation with reality -- has made me want to look into the book: it does seem a promising artistic effect, possibly stimulatory of pleasant philosophical reverie. The author has had such an experience in his own real life, perhaps. Perhaps he can describe it well. Perhaps the truth value of the novel is not all bunk.

Mar 22, 2009

How to use taxpayer funds to narrow programming choices on the radio and another note on bad composers

It seems therefore a little ironic when all these tax-payer funded broadcasters broadcast the same thing all at the same time. Yet this is what happened last night: BBC3 (London), Antena2 (Lisbon), PR2 (Warsaw), Radio France Musique (Paris) and OE1 (Vienna) all played Bellini's Somnambula from the Met. A case of programing laziness, I am sure -- why produce something of our own when here is something ready-made? -- yet, European state-run radio-stations as tools of Yankee cultural domination? Sarko sees it and does not thunder?

Kudos to Nord-deutche Rundfunk Kultur who refused to participate in the general group-do. Instead of taking the easy way out -- just flipping the switch and subcontracting -- they put on an interesting program on the rediscovery of ancient music, Bach especially, in the nineteenth century, and about the important role Brahms played in the rediscovery and popularization of Bach's cantatas.

I couldn't help wondering, all the while, that both Brahms and Mendelssohn obviously had the good taste to recognize Bach's beauty and importance; yet, neither the sufficient talent to compose anything remotely comparable; nor perhaps sufficient objectivity to look at their own work and ask themselves why they bothered. Or -- did they, after a day spent composing, revising and copying their own work look at what they produced and say to themselves: hot damn, this isn't working, is it?

Mar 21, 2009

Some aspects of perception of beauty

The Starowieyski fallacy is the main line of defense of most conservative thinkers today; they often claim it to be somehow an enlightened form of prejudice; it is enlightened because it is somehow cultural and cultural is good because at least some cultural productions are good (the list is usually dull, presenting the tired, usual suspects: Beethoven's Ninth, Raphael, etc.)

What makes in their eyes the defense of some "cultural" practices -- symphonic romanticism, for example, or, more prosaically, fox hunting in Scruton's case -- superior to the defense of other cultural practices -- slavery, for example, or canibalism is not clear. The ground is slippery. The theory, in my opinion, is simply no good unless it can help us distinguish somehow between good and bad cultural practices. It doesn't.

The argument is also flimsy: yes, they say, values are culturally determined but some culturally determined values are important and valuable and must be defended because without them -- the argument seems to imply, we would be somehow reduced to a valueless existence, presumably somehow animal-like. But the implication isn't obvious: all cultures in the world appear to hold some values. The alternative to cultural value set X is not valuelessness but cultural value set Y.

The Starowieyski fallacy is really no more than an attempt to turn on its head the liberal argument that since all values are culturally determined, therefore one should be free to direct rationally the process of selection of the values to appropriate for cultural determination. Contra liberals, the fallacy claims, it would seem, that culturally determined values cannot be rationally adjusted because cultural determination lies at deeper levels of the psyche than any rational thought; and that rational thought therefore can not help but be culturally determined. Yet, while it is true that rational thought is often colored by cultural values, it isn't at all obvious that pure rational thought is impossible. History of western science provides examples of rational thought time and again breaking the culturally prevalent thought patterns.

The truth is that the theorem of cultural determination of beauty is false and therefore both its liberal and conservative versions are bunk. Our perception of beauty is not culturally determined in the usual sense of the word. Rather, it is hard wired and genetically determined. Our ancestors -- our prehuman ancestors, I should like to add since clearly many other animals clearly experience beauty in ways not very different from us (hens, for example, prefer to mate with cocks which humans also find more attractive to look at) -- have evolved these mechanisms over millenia to help us choose better mates, wholesome food and safer dwellings. We can still use the same mechanisms to evaluate mates, food and shelter today; to large extent our preferences in these matters are strikingly similar; but we can also use the same mechanisms for other purposes, for example, to evaluate paintings or sculpture or theater performances. To the extent that in so doing we misapply our brain mechanisms when we do so, the range of our evaluations in these matters shows greater scatter.

Culture comes into play here only to the extent to which culture provides opportunities for looking because experience in evaluating certain types of objects allows us to improve the accuracy of our evaluations. Those growing up in New York City are, by virtue of their life-experience, better equipped to evaluate skyscrapers, for example, than they are to evaluate Ming dynasty porcelain tea-pots. But these cultural effects can be overcome through experience. Recall the famous Melikian dictum that a connoisseur is only as good as the sum total of everything he has ever seen.

Mar 20, 2009

Relief

But his argument then switfly turns to crap because Scruton is not enough of a connoisseur of art to know why he likes what he likes. (A true connoisseur is only as good as the sum total of what he has seen). Scruton, it turns out, simply dislikes abstract (ie. non-figurative) painting and atonal music. The first view is probably uninformed: I cannot believe Scruton, if he looked carefully enough, would dislike Persian arabesques, for example, with their grace, balance, and delicious, rich color; or the equally abstract and Moroccan tiles. I guess that he really dislikes abstract western art for the same reason for which I dislike it: because it is dull-colored, has rough, unifinished surfaces, has been executed with speed suggesting carelessness, is almost always way too big, and nearly always lacks grace; but Scruton misinterprets his dislike, and attributes it to some imagined dislike for abstractness per se, because, well -- most likely because he is a scholar and a philosopher, which means he has not had enough time to make a study of his own likes and dislikes. He has simply not seen enoough abstract painting to know.

His opinion of music is even more embarassingly ingnorant: Stockhausen, whom he pans, is a decent composer, certainly better than Elvis Presley, whom he somewhat sheepishly admits to liking. Scruton's opinions of music, in other words, like those of most of us, are certified ignoramus. I imagine he'd probably like Bruckner's motets, and Mendelssohn's Seven Last Words; though in their case, he would not know enough to be embarassed about publicly pronouncing so. Or perhaps he would not actually like them, but he'd feel constrained by his own theory to pretend that he does and thereby show himself no better than those he criticizes.

Mar 19, 2009

Why do they bother?

When I was finally able to flee, I switched to Vivace, only to be waylaid Esa-Pekka Salonen's songs (Good God!); then quickly over to PR2 where another modern luminary (Magnus Lindberg) was given after a long-winded introduction regarding his sources of inspiration. This (an equivalent of a classical motto in a modernist poem) should have been my warning; such fancy introductions usually announce lousy work. No good work needs the appeal to its sources: it can stand on its own two feet. Really, if you have a good motto, why bother adding anything to it? Just leave it at that.

Please.

And so, yet again I was astounded by the realization how much really horrible music has been written in the western canon. I was reminded of an entry in one of Kapuscinski’s Lapidaria in which he describes a visit to an airport bookstore somewhere and reports seeing masses upon masses of books he has never heard of by writers he has never heard of. They were all ephemera – books now here but gone tomorrow, pulped and forgotten and replaced by the next year’s crop of equally execrable crap.

Why do these people do it? Why can’t these people do something else with their time – I don't know -- bake bread, design widgets, take walks along the sea, spit and catch? What sort of perverse ambition drives them to waste all that precious time doing this awful awful stuff? Do they not realize how short their lives are and how precious every hour?

I mean, really, listening to the Bruckner I could not help thinking how much time he must have taken just writing out the utterly damnable score; all that time, all that time -- and it was no use, no use at all.

Mar 13, 2009

Some surprising facts regarding Real Men

Gibs' legendary A history of Ottoman Poetry (1905), now finally in my hands, is a book Posthumus would have loved. Right off the bat, in chapter one, it characterizes Ottoman Turks as, well, Real Men: fiercely courageous and doggedly loyal, they were men of action not speculation, and, when it came to writing poems, not only did not know how to write, but what to write and, even before that, what to think until a Persian told them. (A devious but effeminate Persian, of course, Gibs kindly forgets to add).

Von Kottwitz suggests Ottoman Turks were brave and loyal but lousy administrators; he misses the obvious point that since their intention was to administer their empire in a manner which would maximize courage and loyalty, and therefore maximize opportunities for the exercise of the same, then, obviously, it follows from the string of bloody wars and rebelions they managed to foment that they administered quite well, thank you.

As one proceeds in this manner in exploring the Real Men lore, one begins to make ever more such surprising discoveries, such as this one: the fellow three seats down from me at the Cafe Colon (Real Men only) is, I am guessing, named Rancho B. Taurus: he has the neck and shoulders of a corrida bull, a shaved and polished head lowered threateningly like a poised battering ram, hands the size of bread loaves, and a brutal facial expression. And he -- sips a sweet rose water milkshake.

Yes, a sweet rose water milkshake. No, he is not having a quadruple espresso with tabasco sauce in a glass -- and is not crushing the glass in his teeth as he drinks it. He is having a sweet rose water milkshake.

Because, well, he can.

From which several Real Mandom aphorisms would appear to follow:

Real Men do whatever they want.

Real Men pay no attention to the rules of Real Mandom.

Real Men do not spend time composing Real Mandom aphorisms.

And, most importantly:

If you ask yourself, you aren't.

Mar 12, 2009

I repeat myself I repeat myself

Your new circle of friends sounds wonderful -- like your high school circle friends regained. You were missing them, weren't you. Do they make you happy? Sounds like they do. If so, it is a good thing. I am glad to hear of it.

No such luck for me. Even less now than ever before. Thirty years of vast interdisciplinary reading in seven languages on three continents and - I am no longer able to have conversation with anyone who can hold my interest at all. My former blog once had a tribe of followers; i had to close it because they all bored me to death.

It would be damnably stuck up of me to say it, no doubt, if it weren't so -- well -- sad. Well, it isn't all that sad: one day, I am sure, I will learn to do without. Or, rather, no, not, that's not quite right: I do without quite well already. Rather, I should say: one day I will learn not to bother to write down what I think for any other purpose than to make a note to myself.

On a good day, I manage to convince myself I have learned that already.

Mar 11, 2009

Dhammapada dixit

"These children belong to me, these riches belong to me", thus says the foolish man, and his life is full of woe. Truly, one does not belong to oneself. Wherefore the children? Wherefore the riches?The Dhammapada is a versified Buddhist scripture traditionally ascribed to the Buddha himself. It's literary value is disputed, but the wisdom of some of its sayings, like the quote above, seems to me beyond doubt.

I once tried to advise to this effect a woman who lived in an unhappy marriage and, as a result, pinned all her love, happiness and hope on her innocent baby son. Foreseeing a miserable youth and adulthood for the boy, a fraught relationship between the two, and a possible heart-rending break up of the sort I have known, I wrote to her: your son is not yours.

She wrote back, Oh, I assure you he is.

Mar 10, 2009

Mar 9, 2009

Michel agrees with Theo

According to him the interest our society pretends to show in eroticism is completely artificial. Most people in fact are quickly bored by the subject but they pretend the opposite out of bizarre inverted hypocrisy. Our civilization suffers from vital exhaustion. In the days of Louis XIV, when the appetite for living was great, official culture placed the accent on denial of flesh and pleasure. Such a discourse could no longer be tolerated today. We need adventure and eroticism because we need to hear ourselves repeat that life is marvelous and exciting; and it is abundantly clear that we rather doubt it.I am not overfond of historicism, but agree with the claim that people are dull (no drive, no ambition, no interests). Plus, the modern overstress of eroticism strikes me also as incredible, but for a different reason: unlike Houellebecq's speaker of the passage above (a priest and therefore presumably celibate), I do know firsthand something about the sex life they have and thus know that most of it is profoundly not worth having, let alone overemphasizing.

I get the impression he considers me a fitting symbol of this vital exhaustion. No sex-drive, no ambition; no real interests, either. I don't know what to say to him: I get the impression that everyone is a bit like that. I consider myself a normal kind of guy.

But then their lives are profoundly not worth having, either, and against the backdrop of the life's worthlessness and boredom dull, repetitive, mechanical, textbook sex is fine, I suppose.

Mar 8, 2009

Last summer in Marienbad

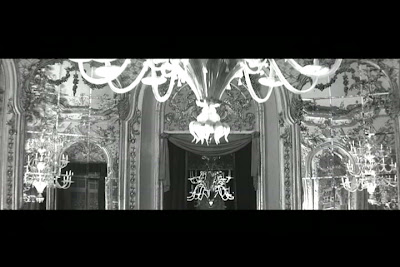

The camera glides slowly, soundlessly through the hall, towards the chandelier and then underneath it. In the film's black and white photography it looks like glowing gigantic thousand-armed squid in some terrifying darkness-deep of the ocean. But it also looks like a Persian calligraphic inscription carved in molten light against a filigree background. As the eye dives beneath the chandelier, the shimmering outline of another appears down the hall.

Mar 7, 2009

A few kilos of dates for a funeral

But the best are the credits written in a weirdly wonderful calligraphy, not to be deciphered by mere beginners like myself without the clues provided by the subtitles. So here they are with the subtitles. Note the final N in Nazaralian, drawn as a circle with its dot inside. It floats far above the line of the script on which it belongs. And Mohsen Namjou, written in two sharply descending diagonal lines. Or Mohsen Tanabandeh written on a curving line, like a saber.

Mar 6, 2009

Michel dixit

There are some authors who employ their talent in delicate description of varying states of soul, character traits, etc. I shall not be counted among these. All that accumulation of realistic detail, with clearly highlighted characters hogging the limelight, has always seemed pure bullshit to me, I'm sorry to say. Daniel who is Herve's friend, but who feels a certain reticence about Gerard. Paul's fantasy as embodied in Virginie, my cousin's trip to Venice... One could spend hours on this. Might as well watch lobsters marching up the side of an aquarium and it suffices for that to go to a fish restaurant.(Michel = Houellebecq, of course).

Mar 5, 2009

Holland dixit

Never has there been so much product. Never has the American art world functioned so efficiently as a full-service marketing industry on the corporate model.Every year art schools across the country spit out thousands of groomed-for-success graduates, whose job it is to supply galleries and auction houses with desirable retail. They are backed up by cadres of public relations specialists — otherwise known as critics, curators, editors, publishers and career theorists — who provide timely updates on what desirable means.

Many of those specialists are, directly or indirectly, on the industry payroll, which is controlled by another set of personnel: the dealers, brokers, advisers, financiers, lawyers and — crucial in the era of art fairs — event planners who represent the industry's marketing and sales division. They are the people who scan school rosters, pick off fresh talent, direct careers and, by some inscrutable calculus, determine what will sell for what.

Not that these departments are in any way separated; ethical firewalls are not this industry's style.

I am glad that others have observed the problem of the interested art critic.

Mar 4, 2009

Souren dixit

Souren Melikian on art objects:

Objects are a better gauge of the true collectors' frame of mind because, unlike paintings, they do not lend themselves to hype as easily as pictures, where world-famous names give auction press offices something that can be celebrated in simple terms.

If someone has never looked at Augsburg and Nuremberg silver gilt vessels of the 17th century, it is impossible to describe in two snappy sentences what makes the greatness of a cup and cover done in Nuremberg around 1630 by Leonhard Vorchammer. By the time you have said that this kind of object is known in German as a Dürer Pokal because its design goes back to Albrecht Dürer in the 15th century, and that this piece of abstract sculpture paradoxically seems to be swirling thanks to its twisted motifs in the central area, you have lost your listener's attention. Add that it is a 17th-century example of Gothic Revivalism, and you will wither under the stare of contemptuous boredom.

I have written extensively about this elsewhere: the unjust hyper-recognition of painting and the hypo-recognition of other decorative arts.

Mar 3, 2009

In a letter to von Kottwitz I wrote today

Atiq Rahimi in a RF interview (I have been listening a lot to RF lately, how much better it is than the BBC -- the BBC struggles to be middle brow, the RF struggles to be anything but that; or perhaps the French middle brow is considerably higher than the English?) surprised me with a tired old saw. The interviewer asked him whether he felt Afghan or French (how European of him); and he said -- duh -- "Afghan in France, French in Afghanistan". Poohlease. I used to say (and think) this kind of drivel when I was 18 -- before I set off on my Asian life (and all that's followed). Now, 20 years later, this strikes me as silly in the extreme. But that's just the thing: Atiq Rahimi is somewhat behind. He's merely bilingual.Von Kottwitz is monolingual and his tri-cultural experience consists in having been born and raised in NY, educated in Indiana, and (briefly) employed in Houston. There are objective limitations to how far our discussion of culture can proceed.

I wonder, btw, whether Barthes -- such a specialist on culture -- was bilingual? (You were probably right to leave him at light petting stage).

Mar 2, 2009

Watercolors

Mar 1, 2009

Innocence

Boulverse, I read on. The images that the reviewer finds troubling are "shots of the girls' legs, those peek-a-boo moments when the camera all but noses under their skirts"; and... small girls in underwear.

A total and absolute mystery.

Peek-a-boo moments? Really?

Nosing under skirts? When? Where?

And then: ten year old children in underwear -- sexy? Does the reviewer have a particularly hairy mind or am I particularly sexually unaware?

But the critique should not surprise; it is wholly and typically American, of course: to the American mind everything seems to carry sexual intent. (They read Lolita in America, don't they?)

It must be very tiring to have such an oversexed mind.

But then, suddenly, there comes a twist: the reviewer closes by recommending a film entitled Fast Times At Ridgemont High as a better alternative to Innocence. It is a better movie, s/he says, because in it "girls have bodies and boys".

I suppose girls having sex is OK, then. And if so, what exactly is the problem with Innocence? Girls not having sex?

I am confused.

The point of the film which the critic so vehemently attacks is actually spelled out in capital letters in the title (for the benefit of the attention deficit disordered): the movie is not about fast times; it is about the time before we even begin to suspect that such a thing as a fast time might exist. It is about beginning to suspect that there are things we do not know. Beginning to suspect and perhaps even beginning to ask, hesitantly and half-heartedly about those suspected things, yet being still prepared to accept "later", "not now", and "forbidden" as final answers.

A reviewer on IMDB puts it like this:

"William Blakes collection of poems on innocence and experience charts the replacing of the former with the latter. He shows us how innocence cannot be appreciated til you are experienced, but how experience completely taints any notion of innocence, and the same is with this precise film."

There is a kind of saudade here, a hopeless longing for the irretrievably lost innocence of the past.

But saudade is not an American emotion anymore perhaps than innocence.

Innocence, by the way, is a very beautiful film. I watched it to the end and then hit the play button and watched it all over again.

I was not sexually stimulated.